Bobbops

Growing up, my grandfather knew everything. As an eternally-curious child (ask my mother how she feels about the question why?), it was a blessing to have him at my fingertips.

Growing up, my grandfather knew everything. As an eternally-curious child (ask my mother how she feels about the question why?), it was a blessing to have him at my fingertips.

He was never showing off, never trying to one-up or well-actually - I think he just had a genuine fascination for the world and everything in it. He wanted to be an architect, but made the 'sensible' move at the time into accounting. He loves jazz and planes and world history and photography.

Every time he'd come home from a trip, we'd gather in the lounge at some point to look at his photos. First, slides in a projector, then eventually a laptop plugged into the tv. Bobbops (being the eldest grandchild, my mispronunciation of 'pops' as a toddler has stuck for the whole family) always has a camera around his neck. I've got a box full of tiny half-frame negatives, about 50 sleeves of 72 frames, including what might have been his first ever roll, waiting to be scanned.

If ever I wanted to know something, he would have the answer. If ever anyone got fed up with my constant but... why? the answer would end up being "ask Bobbops". If he didn't know the answer, he would have a pretty damn good theory.

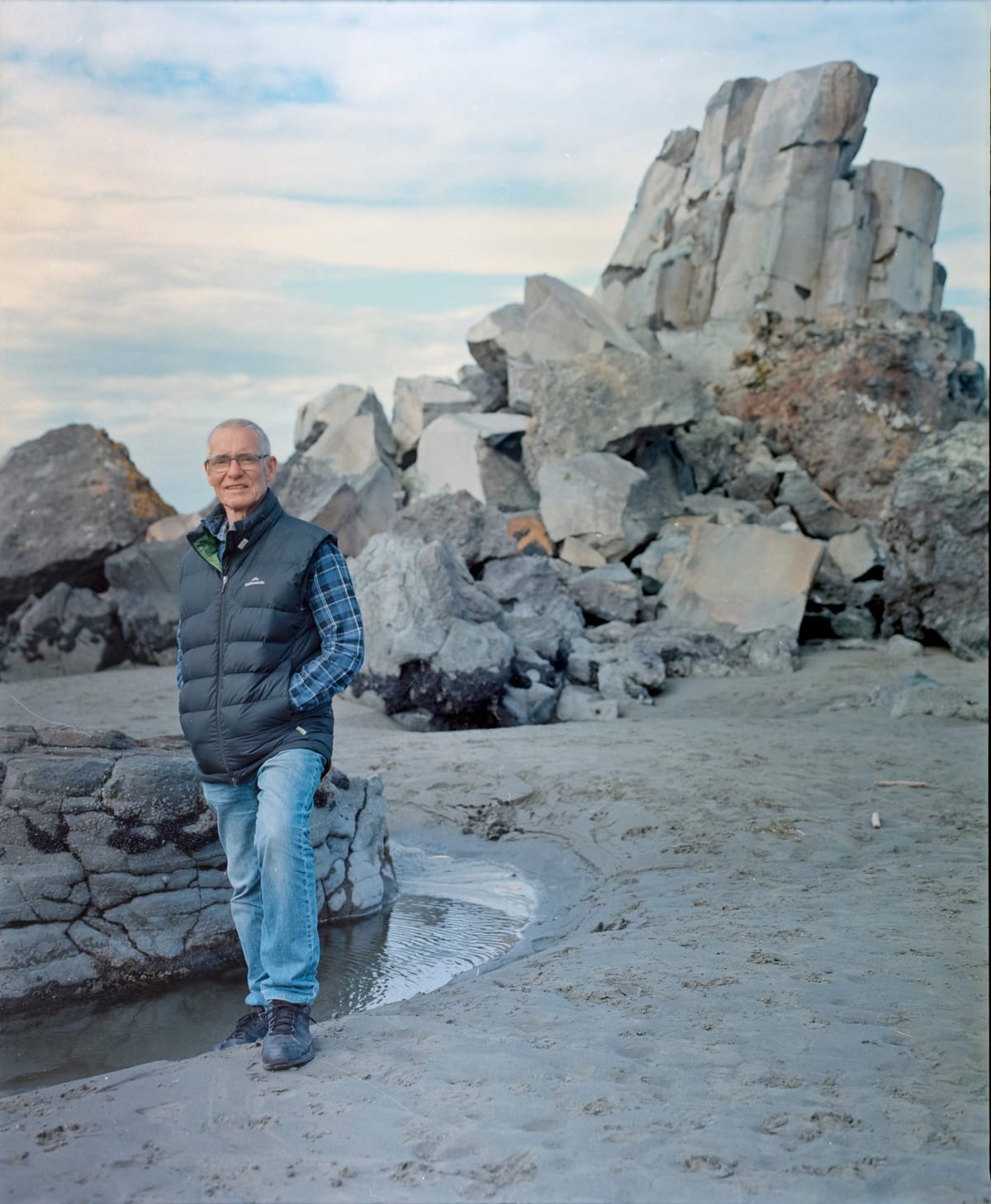

Every Friday, as much as I can, I take him for a walk. We'll go to the beach, to the museum, for a coffee. This week we went to Brooklands, where he grew up, the suburb now mostly open fields, a few remaining houses scattered here and there. He comes and goes, but he generally knows where he is. I think his memory is better than his brain's access to language lets on.

Only four or five years ago, he helped teach me to drive in this suburb. Mum and I took him for a walk on fathers' day, along the path by the lagoon and through the sand dunes, looking over the water on one side and the new subdivisions on the other. It doesn't seem that long ago, and seeing him every week he seems much the same, but looking back on Bobbops four years ago and Bobbops today is jarring. It makes me want to cry.

Looking through my photos of him, the change is more obvious. He's lost a lot of his straight-on perception, relying a lot on his peripheral vision. I have a photo of him with two of his daughters, mum and my aunty, posing, smiling, looking at the camera. It's dated 2018. I'm reading into it, but the photo has captured some kind of intangible presence that's harder to find now.

He's still there - he's still the same person. Some things never change. He no longer has a camera, but I gave him mine a few times on our walks and he grips it like it's always been his. He struggles to find the shutter button, but you try giving a lifelong Nikon shooter a new Canon and see how they deal. He's taken a few shots, but his forward vision isn't there. I'm collecting a folder full of grass and pavement and riverbanks.

He is still perpetually interested in the world. RNZ National is playing in the background every time you visit. He's got a radio on in the lounge and a radio on in his room. And I'm still asking him questions. He remains, more than ever, such a trusted source of knowledge for me, especially now. Unimpeachable. And he does his very best to answer, even when the words evade him. I'm patient. I have all the time in the world.

It's paradoxical, the relationships we have with loved ones with Alzheimers. In some ways, we're closer than ever, our relationship more intimate than it's ever been. When we walk, our arms are linked. One week, we walked around Hagley Park and visited the new magnetic observatory exhibit. I read the signs aloud for him. The next time, we visited the museum-at-CoCA and did the same thing. He listened, intently.

He's very interested in my work. We've had a few long conversations about what I do, who I work for, the communities I serve and the challenges we face. Every time I see him he asks how work is going (and then, almost every time, very soon after, how the cats are). He asks about Mum and my sister and the rest of the family, and about Granny, long-separated.

There's one constant on our walks. Every time I take him out, he'll comment on some buildings, or some landscaping the council has done, or a car - always along the same lines: "now, it's interesting what they've done there... great use of material... very tidy... quite clever really...". He's always engaged in the world around him, especially in its architecture, its engineering, its placemaking.

He's also eternally open-minded, something I hope I've learnt from him. More often than not, those comments will end with something along the lines of "...but it's turned out quite well," or "...people have come round to it." Yesterday, we had a conversation about the adaptability of humans, spurred on by - I think - some roadside wastewater infrastructure.

He remembers every walk. That one took me aback, when I first realised, when he first referred to another walk we'd been on. Even if it's not clear who I am, or if he can't quite get my name, he knows that every week, him and I go for a walk together, and that we drink long blacks and eat a scone every Friday morning. For that, I'm so, so grateful.